What You Need to Know About Abdominoplasty Scarring

Every surgical procedure, whether cosmetic or reconstructive, carries certain risks. One of the most predictable outcomes of surgery is the formation of a scar. Abdominoplasty (commonly called a tummy tuck) is no exception.

Scarring is a natural part of the healing process after surgery. While abdominoplasty scars vary in length, shape, and location depending on the type of procedure performed, there are ways to support healthy healing and reduce the risk of problematic scarring.

This article explains the different types of scars that may occur, what scar placement looks like for each kind of abdominoplasty, how scars change over time, and what treatment options exist if a scar becomes a concern.

Why Abdominoplasty Leads to Scarring

Abdominoplasty involves removing redundant skin and fat, sometimes with tightening of the abdominal wall muscles (rectus plication for diastasis recti). This requires an incision, which heals by forming a scar.

Scarring is not a complication in itself—it is an expected outcome of surgery. However, some patients may develop more visible or symptomatic scars due to:

- Delayed or impaired wound healing

- A genetic tendency to form hypertrophic or keloid scars

- Postoperative complications such as infection

- Tension across the wound during closure

- Lifestyle factors such as smoking, sun exposure, or poor nutrition

Types of Abdominoplasty Scars

Different abdominoplasty techniques result in different scars.

Mini Abdominoplasty

A mini abdominoplasty removes a small amount of excess skin in the lower abdomen. The scar is typically shorter than that of a full abdominoplasty and lies just above the pubic area.

Full Abdominoplasty

A full abdominoplasty addresses excess skin and muscle laxity across the whole abdomen. The scar usually runs from hip to hip, low on the bikini line (just above the pubic hairline). There may also be a scar around the belly button (umbilicus), which is repositioned during surgery.

Extended Abdominoplasty

This is performed when loose skin extends to the flanks or hips. The scar is longer than a standard abdominoplasty scar and may extend beyond the hip bones.

Fleur-de-Lis Abdominoplasty

Often performed after major weight loss, this technique removes both vertical and horizontal excess skin. The resulting scar runs horizontally across the lower abdomen and vertically up the midline of the abdomen, resembling an inverted “T”.

Circumferential Abdominoplasty (Total Body Lift)

This operation addresses loose skin around the abdomen, flanks, back, and upper thighs. The scar runs in a complete circle around the waistline.

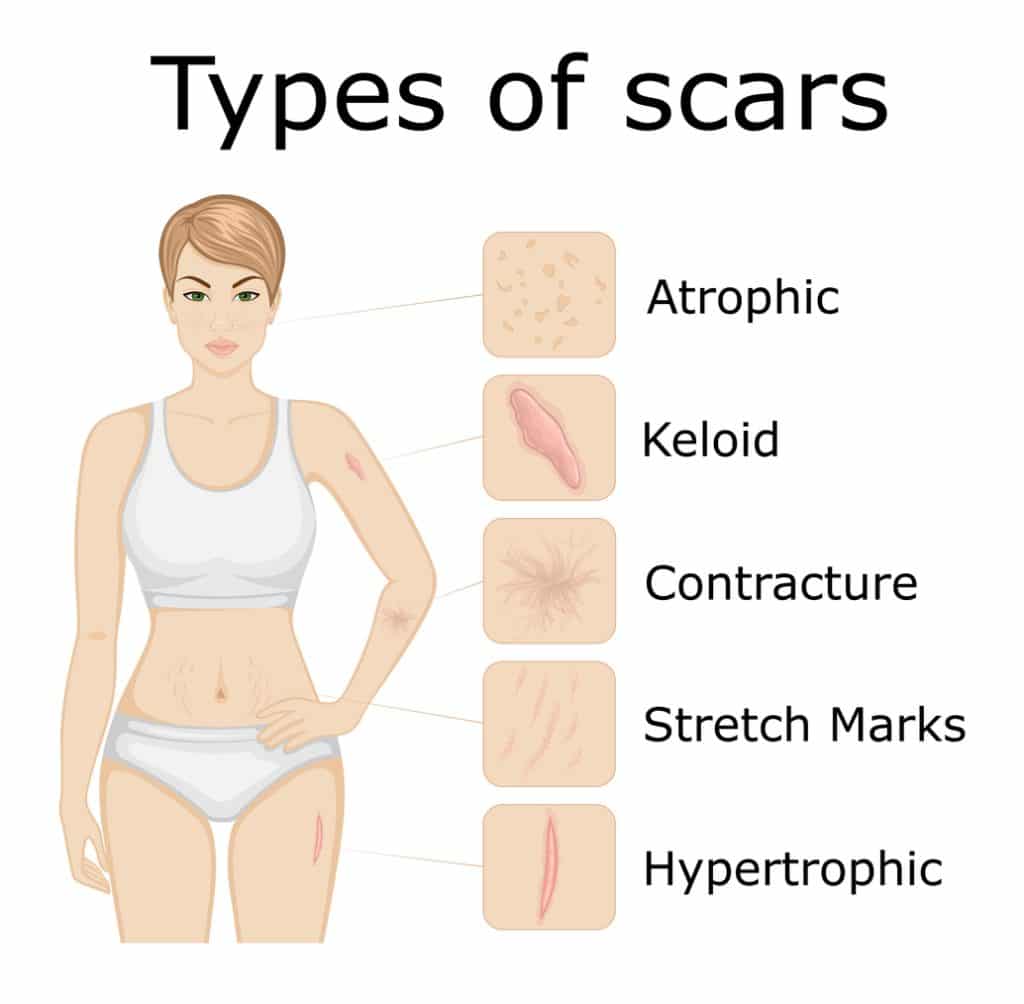

Types of Abnormal Scarring

While many abdominoplasty scars heal smoothly and become less noticeable with time, some patients may experience abnormal scarring. These scars can be thicker, wider, or more visible than expected, depending on how the body heals, genetic factors, and external influences such as wound tension or infection.

Hypertrophic Scars

Hypertrophic scars are raised, red, and thickened scars that remain within the boundary of the original incision. They often develop within weeks of surgery and are caused by an overproduction of collagen during the healing process. While they may feel firm or itchy at first, hypertrophic scars often improve over time, gradually flattening and fading. Treatments such as silicone sheets, pressure therapy, or laser treatment may help accelerate this process if the scar remains prominent.

Keloid Scars

Keloid scars are less common on the abdomen but can occur in individuals with a genetic predisposition. Unlike hypertrophic scars, keloids extend beyond the original incision site and continue to grow over time. They appear as raised, shiny, smooth scars that may be darker than surrounding skin. Some patients experience discomfort, itching, or tenderness in the area. Treatment can be challenging and may include steroid injections, silicone therapy, laser treatment, or in some cases surgical excision with additional preventive measures.

Widened Scars

Widened scars occur when the incision stretches after surgery, often due to mechanical tension across the wound or early return to strenuous activity. Instead of remaining thin, the scar gradually broadens and becomes more visible. Widened scars are usually flat and pale but can be bothersome for patients due to their size. Careful surgical technique, good postoperative wound support, and adherence to activity restrictions reduce the risk. In cases where scars widen significantly, scar revision surgery may be an option once the scar has fully matured.

Tethered Scars

A tethered scar occurs when the scar tissue becomes attached to deeper structures such as the underlying muscle or fascia. This creates a depression or “pulled in” appearance on the surface of the skin. Tethered scars are more noticeable when the patient moves or bends forward, as the skin appears to drag downward. They may develop if the fat layer beneath the incision does not heal properly, leaving the scar to adhere directly to deeper tissue. Surgical scar revision or release procedures can often correct tethering if it causes cosmetic or functional concerns.

Pigmentation Changes (Hyperpigmented and Hypopigmented Scars)

Changes in skin pigmentation are common after abdominoplasty. Hyperpigmented scars appear darker than the surrounding skin due to increased melanin production during healing. This is more common in individuals with darker skin types or in scars exposed to sunlight during recovery. Hypopigmented scars, on the other hand, appear lighter than surrounding skin and may look pale or whitish due to reduced melanin production. While pigmentation changes often improve with time, sun protection is essential to reduce long-term discolouration. In some cases, laser treatments or topical creams may be recommended to improve skin tone uniformity.

How Abdominoplasty Scars Evolve Over Time

Scar maturation is a gradual process.

- Immediately after surgery: Scars are thin and pink.

- One month: Scars may darken, thicken, and appear raised as the body produces collagen.

- Six months: Scars often flatten and begin to fade in colour.

- Twelve months and beyond: Mature scars are usually paler and less visible, though they will never completely disappear.

Minimising Abdominoplasty Scarring

Before Surgery

- Delay surgery if further pregnancies or major weight changes are expected, as this may stretch scars.

- Stop smoking at least four weeks before surgery.

- Choose a FRACS-qualified specialist surgeon with experience in abdominoplasty.

After Surgery

Following your surgeon’s postoperative instructions is critical. Common advice includes:

- Avoid smoking during recovery

- Protect scars from sun exposure (SPF 30+ sunscreen)

- Maintain good nutrition and hydration

- Use compression/support garments as directed

- Avoid heavy lifting or straining the abdominal area until cleared

- Consider moisturising creams or silicone sheets as advised

Treatment Options for Noticeable Scars

If scars remain problematic after full maturation (usually 12 months), treatment options may include:

- Silicone sheets or gels to keep the scar hydrated and improve its appearance

- Laser therapy to reduce redness and improve texture

- Steroid injections for hypertrophic or keloid scars

- Surgical scar revision to re-excise and re-close widened or irregular scars

- Microneedling or dermapen treatments to improve scar texture

Frequently Asked Questions

Will my scar be visible in swimwear?

Most abdominoplasty scars are placed low on the bikini line so they can be concealed by underwear or swimwear. More extensive procedures (extended or fleur-de-lis abdominoplasty) may result in more visible scars.

Do scars move or “drop” after surgery?

Yes. As swelling subsides, scars may settle slightly lower. Surgeons anticipate this and place incisions accordingly.

Can scars be completely removed?

Scars cannot be eliminated, but with time and proper care, most become much less noticeable. Treatments can further reduce their visibility.

Final Thoughts

Scarring is a normal and expected part of healing after abdominoplasty. While scars cannot be avoided, their appearance usually improves over time, and there are strategies to minimise their impact. If you are considering abdominoplasty, it is important to discuss scar placement, healing expectations, and treatment options with a qualified specialist surgeon.

References

- Keaney, T., Tanzi, E. L., & Alster, T. S. (2016). Comparison of 532 nm Potassium Titanyl Phosphate Laser and 595 nm Pulsed Dye Laser in the Treatment of Erythematous Surgical Scars. Dermatologic Surgery, 42(1), 70–76.

- Bhushan, P., Manjul, P., & Lata, S. (2014). Intralesional steroid injections: Look before you leap! Indian Journal of Dermatology, 59(4), 410.

- Gupta, S., & Sharma, V. (2011). Standard guidelines of care: Keloids and hypertrophic scars. Indian Journal of Dermatology, Venereology and Leprology, 77(1), 94.

- Dzubow, L. M. (1985). Scar Revision by Punch-Graft Transplants. The Journal of Dermatologic Surgery and Oncology, 11(12), 1200–1202.

- Thomas, J. R., & Prendiville, S. (2002b). Update in scar revision. Facial Plastic Surgery Clinics of North America, 10(1), 103–111.

- Ogawa, R. (2017b). Keloid and hypertrophic scars are the result of chronic inflammation in the reticular dermis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 18(3), 606.

- Vidal, P., Berner, J. E., & Will, P. (2017). Managing Complications in Abdominoplasty: A Literature review. Archives of Plastic Surgery, 44(05), 457–468.

- Hafezi, F., & Nouhi, A. H. (2006). Safe abdominoplasty with extensive liposuctioning. Annals of Plastic Surgery, 57(2), 149–153.

- Gutowski, K. (2018b). Evidence-Based medicine. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, 141(2), 286e–299e.

- Ho, W., Jones, C. D., Pitt, E., & Hallam, M. (2020). Meta-analysis on the comparative efficacy of drains, progressive tension sutures, and subscarpal fat preservation in reducing complications of abdominoplasty. Journal of Plastic Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgery, 73(5), 828–840.

- Chen, M. A., & Davidson, T. M. (2005). Scar management: prevention and treatment strategies. Current Opinion in Otolaryngology & Head and Neck Surgery, 13(4), 242–247.